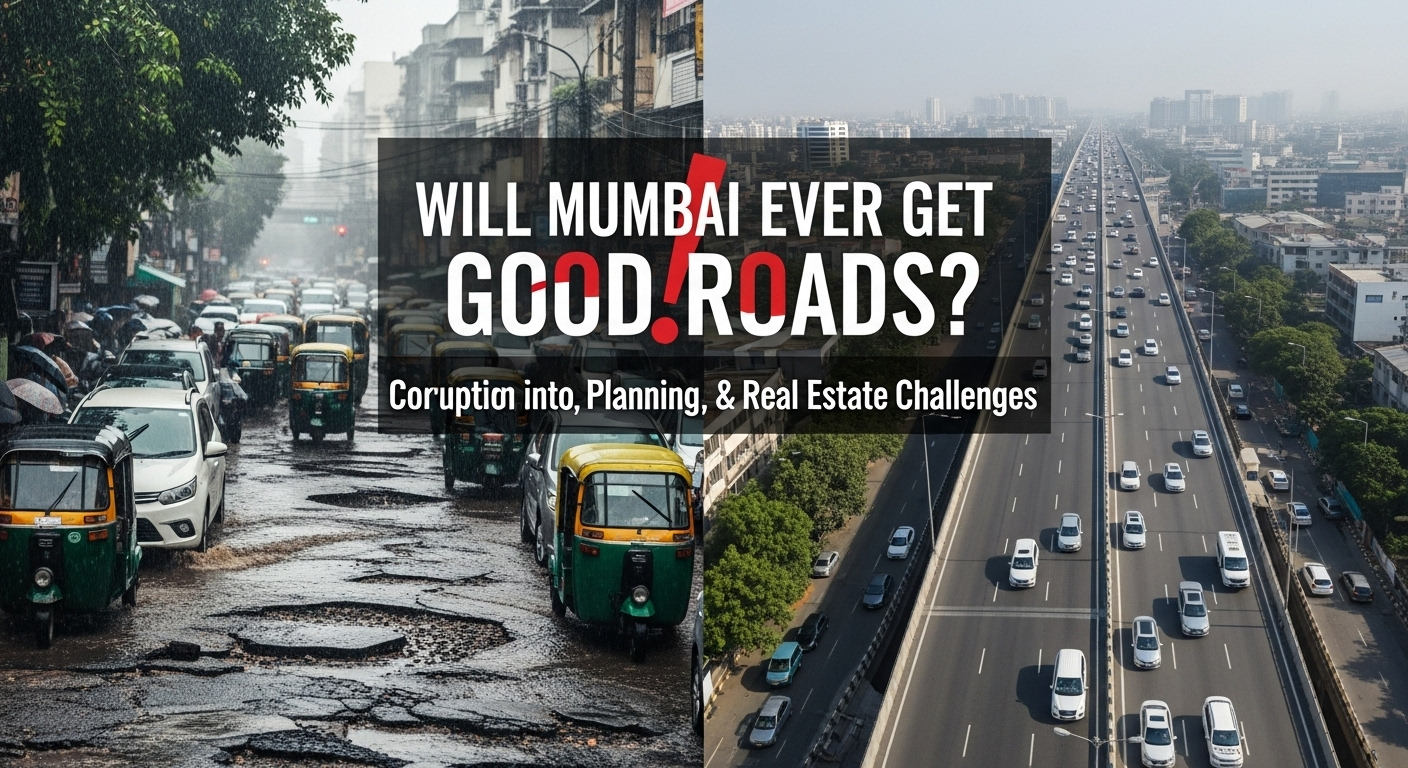

Mumbai is India’s financial capital. It has tall buildings, rich people, and a busy economy. But its roads are in terrible shape. The question “Will Mumbai ever get good roads?” is not just about fixing potholes. It’s about deeper issues like corruption, poor planning, and problems in the real estate sector.

In an interview with Subrat Kumar, who was Mumbai’s municipal commissioner from 2011 to 2012, we explore why the roads are still so bad, what role corruption plays, and if there’s any hope for change.

Mumbai’s Road Problems: A Long-Standing Issue

Mumbai’s roads are famous for being bad. There are potholes, bumpy surfaces, and floods every monsoon. This is surprising because the city’s municipal body, the BMC, is one of the richest in Asia.

Kumar says the problem is a mix of bad planning, corruption, and poor road design. “We didn’t have enough resources, and the roads were designed badly,” he says. He also mentions a scam where contractors simply didn’t build parts of the road but still took the money. He believes only about 15-20% of the BMC’s budget actually goes into real work—most of it is lost along the way.

Corruption: Builders, Politicians, and Bureaucrats

Kumar says the corruption in Mumbai isn’t just from contractors. It also involves a deep connection between builders, politicians, and officials. During his time in office, he tried to stop this.

One big problem was how builders misused FSI (Floor Space Index), which controls how much can be built on a plot of land. Builders often built far more than allowed, charged customers for it, but paid the city much less.

He found that one case involved extra space worth ₹250 crores. His team estimated this kind of cheating cost the city ₹20,000 crores every year and helped only a few rich developers. Honest builders couldn’t compete.

To fix this, Kumar introduced a rule called “fungible FSI,” which allowed more legal construction but with clear rules. Builders were unhappy at first and even accused him of ruining the city’s looks by changing how balconies were counted. But Kumar says balconies don’t make buildings beautiful—smart design does.

Bad Planning from the Start

The problems with Mumbai’s roads and housing also come from bad planning over many decades. After independence, many people moved to Mumbai looking for work. But planning didn’t keep up.

For example, in 1967, the FSI was kept very low—based on British-era thinking—even though demand was growing fast. This led to illegal buildings and slums, which later became vote banks for politicians.

Kumar also points out that no one planned for parking. Buildings didn’t have space for cars, so now people park on the streets. Every piece of land is used for buildings instead of parks or parking areas. In contrast, British planners had a long-term vision and built wide roads like Marine Drive, even when there weren’t many cars back then.

Flooding in Mumbai: Can It Be Fixed?

Mumbai floods every monsoon, partly because of its shape—it’s like a bowl, so water doesn’t drain easily. But Kumar says the flooding can be solved.

After the major flood in 2005, the city was supposed to build eight pumping stations to move water out to sea. Only four are working today. Kumar says if all stations were built and holding areas added near the sea, the city could manage the water like the Netherlands does.

Can Mumbai’s Roads Be Fixed?

Kumar believes Mumbai can have good roads, but it needs proper planning. His idea is to fix one-seventh of the roads each year with help from experts like IIT and supervision from international agencies. In 6–7 years, he believes the whole city could have high-quality roads.

He supports using concrete for major roads due to heavy rain but says not every road needs it. Good asphalt roads can last 15 years if built properly.

He also thinks the city should give road contracts to just one capable company. Small contracts lead to poor work because contractors don’t invest in good machinery. He points to a social media post that compared BMC’s roadwork to the Stone Age—showing the urgent need for modern equipment.

Affordable Housing: Is It Possible?

Mumbai’s housing is so expensive that even small homes are out of reach for most people. Kumar says the idea of “affordable housing” in Mumbai is not realistic. A 300 sq. ft. flat costs over ₹1 crore, while most people earn only ₹10,000–₹20,000 a month.

He suggests increasing FSI for small flats to create more homes and spread the land cost over more units. But even then, the main issue is that builders often build homes where there’s no demand, not where people need them.

Missed Chance: Mumbai Trans Harbour Link

The Atal Setu bridge was built to connect Mumbai and Navi Mumbai. But Kumar says it hasn’t helped as much as it could have. He had suggested adding pillars to support a future railway line on the bridge, to make it useful for public transport. That didn’t happen.

He also says the toll on Atal Setu pushes people to use the older, toll-free Vashi bridge, reducing the new bridge’s impact.

The Coastal Road: Some Success, Some Problems

Kumar helped plan Mumbai’s coastal road to reduce traffic inside the city. It’s partly built now and has already reduced traffic in some areas by 60%. However, parts of the road are bumpy because they were built quickly during the monsoon.

Still, he believes it can improve travel times and make the city more productive. “People waste 4–6 hours commuting. That hurts Mumbai’s economy,” he says.

Changing the Mindset: Not Just Buildings

Mumbai’s focus on turning every bit of land into buildings has hurt its growth. Kumar says the city needs more parks, playgrounds, and parking areas.

He says no cars should park on roads. Instead, create proper parking spots every 500 meters, based on how crowded the area is. Also, don’t count mangroves or slums as “open spaces”—only usable areas should count.

Kumar’s Legacy: Tough but Fair

Kumar brought big changes, though not everyone agreed with him. He didn’t face threats because he targeted systems, not individuals. He says, “I’m not anti-builder. Builders provide homes. But bad practices, whether by builders or officials, need to stop.”

Under his leadership, the BMC earned more through taxes and clear rules. Still, he regrets not doing more for education and footpaths. He had planned to let NGOs run BMC schools with performance-based funding, but his time ran out. On footpaths, he wanted to organize hawkers into special zones to balance their needs and public space.

Can Mumbai Be Fixed?

Kumar believes Mumbai’s problems can be solved—but it won’t be easy. It needs political will, good leadership, and long-term thinking.

He dreams of a city with solid roads, proper drainage, affordable housing, and more public spaces—not just buildings. With honest and forward-thinking leaders, Mumbai has a chance to become the world-class city it’s meant to be.